One of the scenarios that could possibly develop in Ukraine over the next few days is outright war between Ukraine and Russia. Tensions show few signs of defusing, and “Will they or won’t they?” seems to be the big question at the moment. Of course, war is obviously the worst case scenario, for both Russia, which would further alienate basically the rest of the world, potentially leading to Cold War Part 2, and Ukraine, which would probably hang on for awhile but eventually lose.

Over the last several days, there have been the usual grumblings in the form of military maneouvers that world powers like to pull when they feel the need to express themselves. Russia has been massing troops at the Ukrainian border, and the Ukrainian government has announced that it will be holding joint military exercises with the UK and US (although the UK seemed hesitant to confirm this statement). Meanwhile, US Vice President has announced that the US is considering sending ground troops to the Baltics for more military exercises and has tasked twelve extra F-15 fighter jets to NATO patrols in Poland and the Baltics. However, rations promised by the US have been slow to arrive in Ukraine, and Obama has stated that the US won’t “be getting into a military excursion in Ukraine” and has made it pretty clear that America prefers the sanctions route to any sort of military engagement.

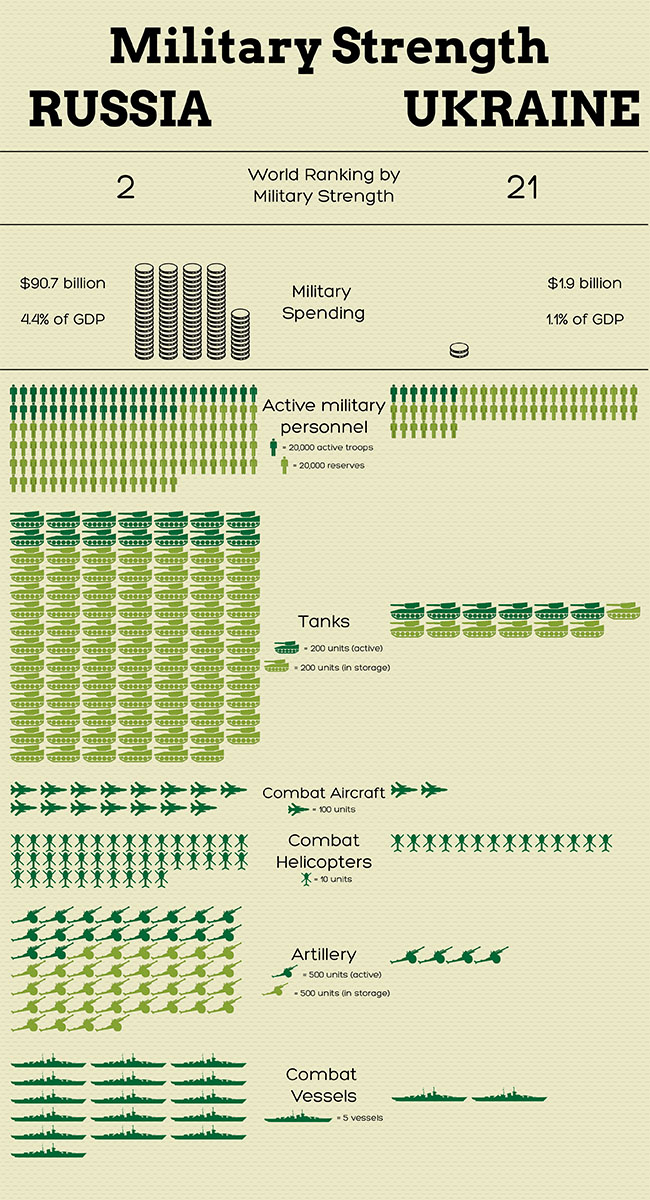

But this would [hypothetically] be a war between Ukraine and Russia. Yesterday, I made an infographic showing the vast difference in military ability between Russia and Ukraine. Some of Russia’s troops are stationed in its Far East and along the border with China, and small numbers are in the North Caucasus (stabilising South Ossetia and Abkhazia) as well as Central Asia. However, it’s still expected that Russia would be able to muster a significantly larger force than anything Ukraine could produce in the event of a war.

Although Ukraine increased military spending in recent years, administrations have typically failed to deliver the necessary budget required to modernise equipment and adequately train their conscripts. While recruiment numbers have been strong for the newly created National Guard, separate from the police and military, it is unrealistic to expect that these individuals would be fully trained in the immediate future.

The perception amongst Ukrainian soldiers seems to be that, in the case of a war with Russia, they will fight. At the same time, there seems to be some sort of expectation that the US will send military assistance.

History time. Prior to World War II, France and the UK had signed several treaties meant to protect Poland’s territorial integrity. In 1925, as part of the Locarno Treaties, France and Poland signed a treaty pledging mutual assistance in case of an attack by Germany. Meanwhile, in August 1939, Great Britain and Poland created the Anglo-Polish military alliance, which specified in a secret protocol that Britain was to aid Poland, also in the event of an attack by Germany. But when September rolled around and Hitler made his move, France and Britain were reluctant to send aid. The reality was that the governments of both nations had decided months earlier that defeating Germany was more important than defending Poland – that is, why waste resources on defending a strategically difficult position when those resources would probably be necessary for national defence later on in the war?

When I look at the current situation in Ukraine, I see echoes of Poland in 1939 (note: I am NOT comparing Putin to Hitler. I do not think that is an accurate comparison.). Justifying a war in Ukraine would be difficult for the US. Russia’s army is a formidable force – the US might be ranked #1 in the world in terms of military strength, but Russia is #2 and Russia would have the home field advantage. It would be much easier for them to move and supply troops than it would for the US, who would have to shift troops from Germany, Spain, Italy, and America. The US would have difficult penetrating the Black Sea stronghold that Russia has built, being forced to send vessels through the bottleneck of the Turkish Straits. In order to land troops and planes, the US would have to persuade its NATO allies to let it use their military air bases. Heavy artillery would have to be shipped from the US, and supply lines could take weeks or even months to negotiate. Russia has ample supplies of fuel – where would the US get the necessary power for its army if Ukraine’s energy supplies from Russia were cut off (which, in the event of a war, they most likely would be)? The US has spent the last 13 years at war in the Middle East and Afghanistan. There are still 40,000 troops in Afghanistan, personnel and equipment are tired, and the American public would most likely be unenthusiastic about another war, especially given the lack of overall achievement in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Finally, as Russian TV host Dmitry Kiselyov pointed out, Russia is the only nation in the world capable of turning the US into “radioactive dust”. Russia has an arsenal of 1,800 nuclear warheads that are considered to be ready for use on short notice and a stockpile of 4,500 more. Many of these are intercontinental with ranges of up to 16,000 km, fully capabable of hitting the west coast of America or Western Europe. Since Russia and the US acquired nuclear weapons, became superpowers, and began to clash, they have preferred to fight proxy wars (see: Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan in the 80s, Nicaragua, etc.), since the alternative is basically to bomb each other into oblivion (apparently nuclear holocaust is preferable to losing). The closest that the US and Russia/USSR have come to war was during the Cuban Missile Crisis – an escalation which neither Putin nor Obama is likely to want to repeat. In World War I, global powers learned that upholding treaties wasn’t really worth the cost if they ended up destroying you, your enemy, and everyone in between. It’s unlikely that the West would see a nuclear holocaust as an acceptable price to pay for upholding the Budapest Memorandum.

Without US or other involvement, Ukraine is unlikely to be able to win a land war against Russia. Geographically, Ukraine is, like Poland, a large, flat country with few natural defences. Here’s a map (from 2008, but doubtful much had changed on the Ukrainian side, although I wouldn’t count on the numbers for accuracy) showing how its forces are distributed, taken from a Russian military blog:

Note that most of Ukraine’s military might is concentrated in the Western half of the country, a Soviet-era tactical holdover meant to defend against a NATO attack from the West. Now, here’s a map, also from a Russian military blog, showing Russian’s theoretical invasion plan:

Any invasion would (obviously) most likely come from primarily from the east, with contributions from the south via Crimea and potentially the north via troops stationed in Belarus. I’m sure the Ukrainian army would fight. Ukraine has developed quite a sense of national identity of late, and its troops supposedly have a strong esprit de corps. But Ukraine will lose. It will not have access to the fuel and human capital it needs to stage a convential ground war. Russia will throw manpower at the problem, as it always has. Ukraine has a history of nationalist guerilla warfare (whose dark side I will ignore here) dating back to WWII, and it is considered to be the most effective form of fighting against larger forces. Already, people in Ukraine’s east, which doesn’t even have the same partisan mythology of the west, are arming themselves in preparation for an invasion. It’s possible that the war could go the way of the Afghan-Soviet War, but not without a significant casualty count.

A Russian-Ukrainian war is literally the worst-case scenario for both sides. It is almost guaranteed to be long and bloody, given Ukraine’s spirit and tenacity in the face of Russia’s vastly superior conventional military abilities, and the rest of the world is unlikely to want to become involved militarily in any significant role to ameliorate the situation. War would further isolate Russia and exacerbate its paranoia about being constantly under threat from the rest of the world (which leads to it making “aggressively defensive” moves like the annexation of Crimea). Given the troop levels massed on Russia’s western border, conflict is a distinct possibility – hopefully, Western leaders will have the sense to come up with an effective, unified response to Russia (for example, introducing transparency to destabilize the concentrated Russian leadership, or broader, far more severe sanctions a la Iran in a worst case scenario) which will demonstrate that disregarding territorial integrity will not be tolerated in the 21st century.